Other Ex-Presidents Who Tried to Recapture the White House

In the next two years, Donald Trump hopes to make history as the second President to ever recapture the White House after losing an election and leaving power.

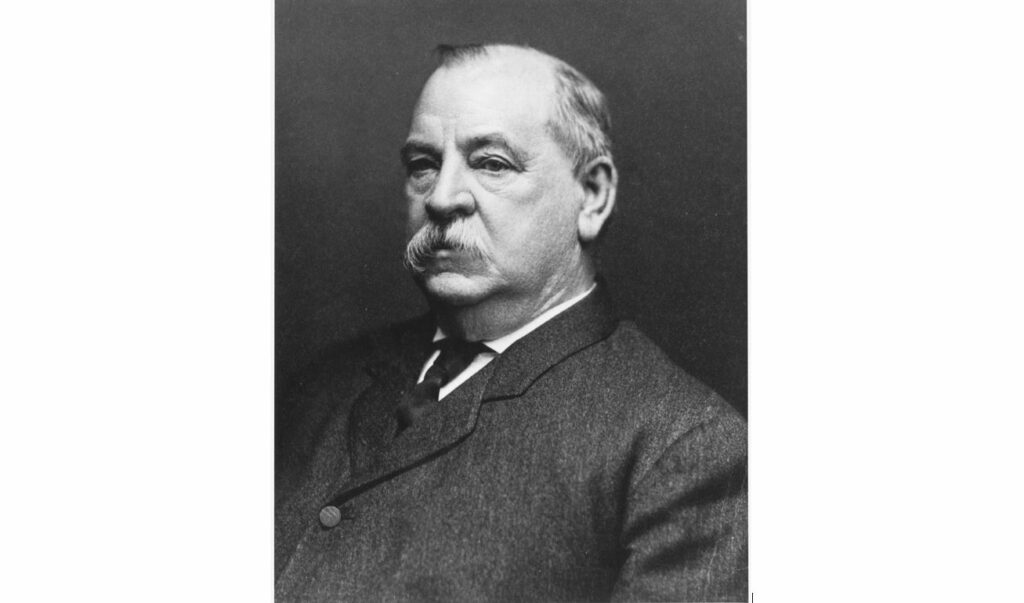

Only Grover Cleveland succeeded in accomplishing such a comeback with his third presidential race in 1892, but three other chief executives ran serious but unsuccessful campaigns to reclaim the nation’s top job after they had left. A quick consideration of their experiences can provide useful context for evaluating the problems and possibilities of Trump’s current efforts.

Few presidents brought as varied and impressive a resume to the White House as Martin Van Buren. He had served as a New York state senator, United States Senator, Governor of New York, Secretary of State and Vice President of the United States before taking charge as Andrew Jackson’s chosen successor in 1836. Unfortunately for him, a devastating financial crisis (“The Panic of 1837”) led to a major depression and ruined his popularity in his first year in office. He nonetheless sought re-election but lost in a landslide (234 to 60 electoral votes). He tried his first comeback four years later but at the Democratic convention, despite his early delegate strength, lost the nomination to the dark horse candidate (and ultimate victor) James K. Polk.

A battered political veteran at 66, Van Buren felt increasingly estranged from the Democrats he had long led, particularly regarding his principled opposition to the spread of slavery in territories and new states. In 1848, he accepted the presidential nomination of the newly organized Free Soil Party and, with Charles Francis Adams as his running mate (son of one president and grandson of another), made a spirited race to return to Washington. The Free Soilers didn’t carry a single state but drew 10% of the overall electorate. Van Buren polled strongly enough in his home state of New York, in fact, to tilt the state away from the Democrats and to enable the election of Whig candidate Zachary Taylor.

When President Taylor died of a still mysterious stomach ailment two years later, Vice President Millard Fillmore took his place and became the next chief executive to attempt a comeback campaign after leaving office. A little-known Congressman from upstate New York, Fillmore had never even met his running mate, the war hero General Taylor, before their mutual election. After his ascension to the presidency, Fillmore tried to secure the Whig nomination for a term of his own in 1852 but lost to another celebrated commander of the Mexican War, General Winfield Scott, affectionately known as “Old Fuss and Feathers.”

In the first months of his retirement, Fillmore suffered terribly from the death of his wife and their daughter, before seeking comfort and distraction with a year-long European tour. In the midst of his travels, he received an offer from the rabidly anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, American Party (widely known as the “Know Nothings”) to become their candidate for president in 1856. He accepted by mail and ran on a platform that restricted all public offices to native-born, non-Catholics and extended the residency requirement for citizenship to twenty-one years. With support from remnants of the collapsing Whigs, Fillmore managed an astonishing 21% of the popular vote but carried only the state of Maryland.

The most celebrated of all the failed attempts at White House recapture involved one of our widely admired Mount Rushmore presidents: Theodore Roosevelt. Unlike the other leaders who eventually attempted post-presidential returns, he won his initial campaign for re-election. Having taken office after the assassination of William McKinley in 1901, Vice President Roosevelt won a landslide victory for a full term of his own in 1904. He promised at the time of his victory that he’d make no further bid to continue his presidency after serving nearly eight years, and designated William Howard Taft, an esteemed leader of the cabinet, as his successor. Retirement, however, didn’t suit the peripatetic TR (only 50 when he left the White House) who after a triumphal European tour decided to challenge Taft for the Republican nomination of 1912.

Despite Roosevelt’s predictable success in a series of recently instituted primary elections, the GOP establishment controlled the most delegates at the Chicago convention and mandated the incumbent’s renomination. TR’s indignation produced self-righteous fury and a determination to run as a “Bull Moose” candidate of the swiftly organized Progressive Party, announced with the celebrated proclamation: “We stand at Armageddon and we battle for the Lord.”

Inevitably, the Republican division handed victory in that end-of-the-world battle to Democrat Woodrow Wilson, but Bull Mooser Roosevelt still carried 6 states and 27.4% of the popular vote. While he could feel personal satisfaction in out-polling the hapless incumbent, his dramatic drive for validation and a new term of office never came close to success.

These consistently disappointing outcomes for some of the more colorful ex-presidents in our past, raise questions worth pondering for Trump and his principal advisors. What enabled Grover Cleveland, alone among the Donald’s predecessors, to succeed in making a successful return to the presidency?

For one thing, he never contested the painfully close outcome of his first bid for re-election, even though he actually won the popular vote against Republican Benjamin Harrison (48.6% to 47.8% nationwide) and lost the state of New York by only 1.09% and with it, the election. Cleveland made no claims about a stolen or “rigged” result and, as his 2013 biographer John M. Pafford explained, he “refused to look back. He was stubborn, but he did not become bitter or depressed over the outcome of the election. He had fought to win. Now he accepted his loss with grace and got on with his life.”

For the First Lady, at least, that almost certainly meant preparing for another race for the White House. The 23-year-old Frances Folsom Cleveland (who had married the bachelor president midway through his first term) reportedly admonished the executive mansion’s household staff on the stormy day of their rival’s inauguration, that they should take good care of the premises because the Clevelands expected to return in four years.

To make that development possible, the former president, though still in his early 50s, consciously played an elder statesman role, rising above the ideological divisions in his party. That approach helped the Democrats achieve a spectacular and unequivocal triumph in the midterm elections of 1890, gaining a record-breaking 86 seats in the House which, at the time, contained a total of only 332 members– a glaring contrast to the disappointing midterm performance of Trump’s divided party in 2022, just a week before he chose to announce his third White House candidacy.

At the Chicago convention of 1892, Cleveland won the presidential nomination on the first ballot, a striking show of unity at a time when that selection required two-thirds of all delegates. In the general election, the Democrats also benefited from a strong showing by the rising “People’s Party” (or Populists) who drew particular strength from states in the West and the rural Midwest where Republicans had traditionally dominated. The Populist candidate, former Congressman James B. Weaver, won five states, including four in which Cleveland and the Democrats declined to appear on the ballot (North Dakota, Kansas, Colorado and Idaho) to help the People’s Party and deny the GOP those electoral votes.

In the end, Cleveland won handily in terms of the Electoral College (277-145) while drawing a slightly lower percentage of the popular vote than he had in both of his prior races.

This experience, together with that of the other “comeback candidates” who sought to retake the White House after a prior defeat, suggests that it’s simply not true to assume that when it comes to former presidents “absence makes the heart grow fonder.”

This lesson pertains pointedly to the current Trump campaign, where the candidate’s announcement speech on November 15th described his previous term as a golden age to which the public would naturally seek to return. But this would require a dramatic increase in the percentage (46.8%) who voted for him in 2020 – in other words, millions of voters would need to change their minds about Trump and the leadership he offers. As prior experience consistently demonstrates, once the public has already passed judgment on a chief executive’s presidential performance it would be hard to imagine how out-of-office activities could ever alter that verdict in his favor.

Considering Donald Trump’s well-publicized behavior since leaving the White House in January 2021, there’s scant reason to suspect that he would somehow make himself an exception to that historical rule.